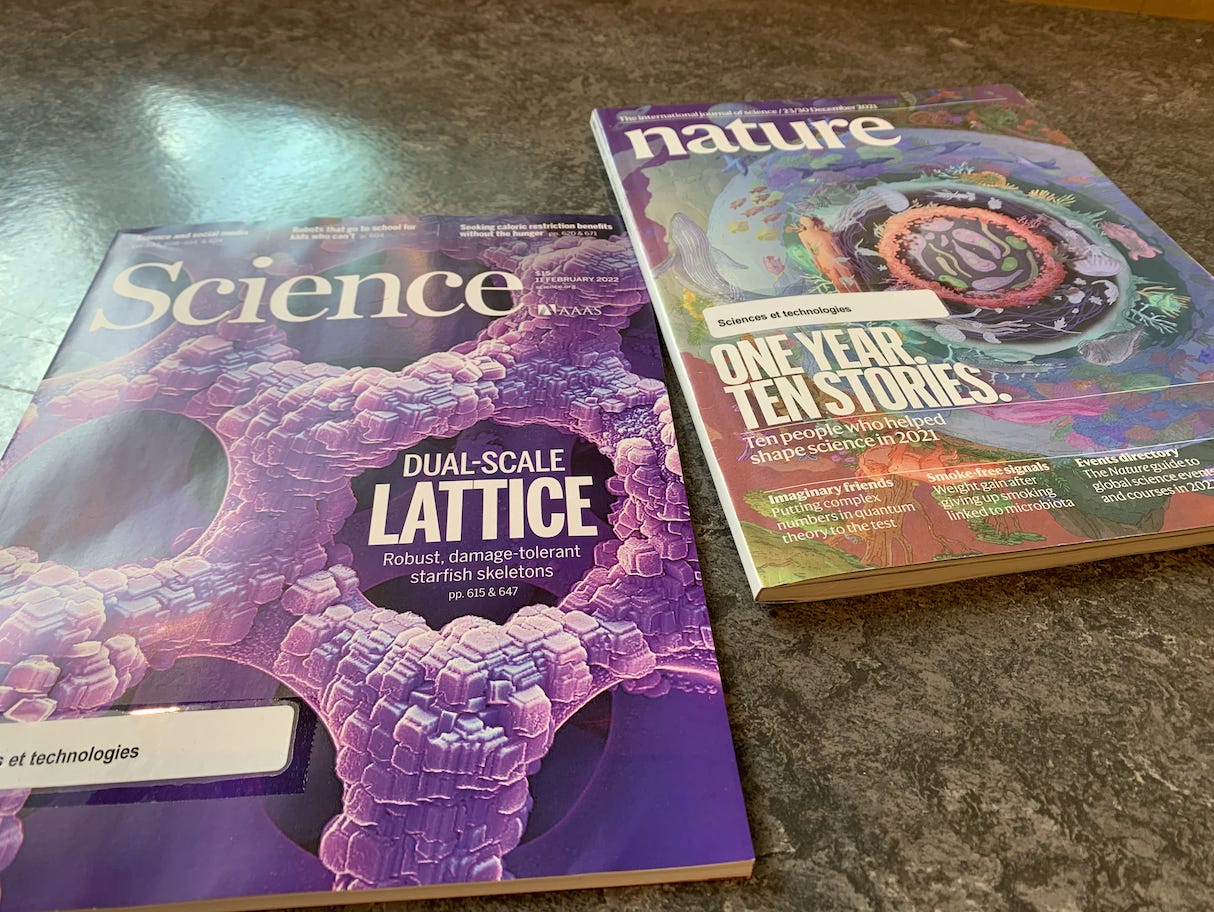

Browsing Paper Copies of ‘Nature’ and ‘Science’

What the top journals feel like in physical form

Most people’s experience of scientific papers, if they have any, consists of downloaded PDFs and articles read directly on the websites of publishers. But of course “papers” are called that because they used to be printed on, well, paper. And some still are! Including everyone’s favorite über-prestigious weekly generalist journals, Nature and Science.

I wanted to get a better feel for what these two journals are in print, so I went to my local library and picked up a relatively recent copy of each. (I also wanted to check out Cell, but they didn’t have it; this isn’t a university library.) Here’s a little write-up of the experience.

Science

The volume 375, no 6581, 11 February 2022 issue of Science has 107 pages and a cool purple cover that shows the structure of a starfish skeleton from up close. It opens with some ads and then two editorials by the same editor-in-chief somehow.

The rest of the magazine is organized in three sections: News, Insights, and Research. The News section starts with two pages of short science news (one paragraph each) followed by six news articles (about one page each). The section is capped off by a 4-page “feature” article about robots used in education for children who are stuck at home; in other words, a piece of relatively long-form journalism. All of this is written not by researchers, but by science journalists.

The next section is called “Insights,” whatever that’s supposed to mean. It opens with two pages of random opinions by scientists on whether social media is good or evil (final score: 15 for good, 8 for evil). The next two articles are on the same theme of social media and are apparently authored by experts on science communication.

What follows is five Insights “perspective” articles that confuse me a little bit. They’re all essentially summaries and popularizations of articles found later in the Research section. Their authors seem to be specialists in the relevant fields, but they’re not the authors of the Research articles. For instance, one is about the cover issue, starfish skeletons: Starfish grow extraordinary crystals, by Stephen T. Hyde and Fiona C. Meldrum. It refers to another article titled A damage-tolerant, dual-scale, single-crystalline microlattice in the knobby starfish, Protoreaster nodosus by Yang et al. Hyde and Meldrum are professors of chemistry and materials science, but they’re not among the authors of the research article. The same pattern holds for the next four perspective articles. So it seems that Science is asking scientists to write about other scientists’ work in a more accessible way. This is good!

The Insights section ends with an obituary and two book reviews, and then we get to the main attraction: the Research section. First, we have a dozen very short summaries of papers either from the Science family of journals or from the wider literature. Then, four 1-page “research articles summaries” that read as complete but very short papers, each with an intro, a rationale, the results, a conclusion, and one figure. They all state that you can read the full article online. Here’s an example. The “Structured Abstract” on that page is what appears in print (and that’s all you’ll get if you don’t have a subscription to Science).

There are 60 pages left to this issue — more than half — when we finally get to the “research articles.” Those are long: 7-8 pages in print. There are also only two of them. I assume they’re the most prestigious part of the magazine, since they’re not shortened in any way and their tiny number means it must be difficult to be selected. Indeed, the Science website’s page on Information for authors mentions that they “are expected to present a major advance.” Slightly shorter (4-5 pages) are the remaining eight “reports,” including the starfish one I mentioned earlier. These have to “present important new research results of broad significance.”

At the end of the issue, we get a few more ads and a cute 1-page personal story by some scientist.

Nature

The first thing I notice is that Nature is thicker than Science. This issue — volume 600, no. 7890, 23/30 December 2021 contains 209 pages, so about twice as many as its American counterpart. (Nature is a British journal.)

Nature opens with a (single) editorial, a “world view” (an opinion piece by some prominent person) and then some news, first “in brief” and then “in focus.” Since this was the last edition of 2021, we get a cool “best images of the year” thing, and then a 14-page-long feature that contains 10 short pieces on scientists who illustrated themselves last year. This feature, not a research article, is also what’s on the cover of the entire issue.

The News and Views section that follows seems to be the equivalent of the Perspective articles in Science: seven short, clear pieces written by experts about research published by other authors elsewhere in the issue. After this comes a 2021 retrospective (I’m starting to think this wasn’t a good example of a typical issue) and then we get the first “Article.”

“Articles” in Nature are 3-6 pages long, similar to the “Reports” in Science There doesn’t seem to be anything longer. But there are many more: twenty-six in this issue. Even if they’re short, they’re full articles, as opposed to abridged versions of something longer on the website. So in a way, Nature seems more egalitarian than Science: nothing is given more status than the rest, and all articles are expected to have a similar format.

The issue ends with several articles on science as a workplace and professional activity: there are pieces on the state of scientific work, issues with alcohol at science events, and some tips for event organizers as well as people who want to tell more compelling stories in their presentations. (“State your main finding in your title, and don’t forget to use the word ‘but’.”) There’s a calendar of networking events, a bunch of ads throughout, and, at the very end, a cute 1-page personal story by some scientist.

Conclusion

Nature and Science were explicitly created with a dual aim: communicate results between scientists, and from scientists from the public. Even though they are now known more for their research articles — and the prestige that they offer to the few researchers who manage to be selected — they still carry their mission of popularizing science, partly through those hybrid “perspective” and “news and views” papers. This seems like an overall good thing.

One thing that is more difficult to do online (despite the invention of the web browser!) is simply browsing through and randomly stumbling on interesting articles. This was actually a concern for the Nature staff back in the 1990s: according to the book Making Nature, they thought that the advent of the electronic journal would lead to less browsing. I think they were right to a large extent. Even though I wasn’t intending on reading any of the articles, my leafing through print copies made me read a few short things that seemed interesting and that I would likely never have encountered otherwise.

I’ve known for years that Nature and Science exist in print. Yet I don’t think I ever saw or opened a copy, even though I have a couple of science degrees. I’m guessing that my experience is not unusual. It may be a good idea for researchers who deal with disembodied papers all the time — both as readers and as authors — to remind themselves what papers actually are, or were.

Browsing paper copies of jawws https://pasteboard.co/Raaal0AibRJd.jpg